Mercer Music at Capricorn in Macon, Ga.

In some ways, it feels like the blink of an eye for Dickey Betts. "Then I look at my big white beard and realize it was a long time ago," Betts says with a rascally laugh, calling from his Osprey, Fla. living room.

It's been 50 years since the self-titled debut album by Allman Brothers Band, the Southern rockers with whom Betts found fame as a gifted and expressive guitarist, singer and songwriter. That seven-track album showcased the Jacksonville, Fla.-founded group's blues, psychedelia, jazz and country fusion, crystalized on songs like dark-epic closer "Whipping Post." The LP also established the Southern rock template: Relatable-rogue songs of travel, pain, love and beauty; swaggering musicality; and transportive guitars for days.

Released in November 1969, The Allman Brothers Band was the first album issued on Capricorn Records. The Macon, Ga. based imprint would become synonymous with Southern rock, thanks to iconic hits by the Allmans, Marshall Tucker Band, Wet Willie and others. On Tuesday (Dec. 3), the legendary studio celebrated its 50th anniversary with a grand re-opening as Mercer Music at Capricorn.

Capricorn Records was founded in 1969 by Phil and Alan Walden, two Georgia brothers who'd been working with soul acts like Otis Redding, and Frank Fenter, a South Africa-born, U.K. Atlantic Records executive who brought salesmanship and record biz experience. The Waldens pivoted to rock after friend and publishing partner Redding died in a 1967 airplane crash.

At Capricorn, Alan toggled between management, accounting and production hats. The flamboyant, larger-than-life Phil Walden became the label's face and driving force. "My brother could sit down in a meeting, drink a half bottle of scotch and get so damn creative that it was just amazing," says Alan, calling from his lakefront home outside Macon.

Phil Walden and Atlantic exec Jerry Wexler devised Capricorn, named for their shared astrological sign, to feature young, long-haired guitarist Duane Allman. Phil became enamored with Allman's playing after hearing his electrifying solo on Wilson Pickett's "Hey Jude" cover, recorded at Muscle Shoals, Ala.'s Fame Studios. He arranged to purchase Allman's contract from friend and Fame impresario Rick Hall.

"Phil Walden's idea," Betts says, "was to take Duane and have a trio like Jimi Hendrix or Cream or one of these power trios like that." The resulting Duane solo tracks weren't bad. They just weren't special. However, whenever Allman sat in at gigs with Betts and bassist Berry Oakley's band, The Second Coming, it was incendiary. The classic Allmans lineup was assembled from there: Duane, his blond younger brother Gregg Allman on vocals and keys, Betts, Oakley and dual drummers "Jaimoe" Johanson and Butch Trucks. "That's what we took to Macon," Betts says, "and when Phil heard that whole six-piece band he went nuts over it." Others were less enthusiastic. "Record companies used to come to see us," Betts says, "and would say time and time again, 'All their songs sound alike. They don't dress up and don't have a frontman. They just get up there and play.'"

After Walden and Wexler cut a deal for distribution, The Allman Brothers Band was tracked at New York's Atlantic Studios. Betts recalls using a Gibson 335 guitar and Marshall amps on the sessions. "We did a good record, but we were like fish out of water, really. Most of us had never been to New York before." In addition to "Whipping Post," the LP is known for the yearning opus "Dreams." Betts' favorite cuts though are "Don't Want You No More" and "It's Not My Cross to Bear," the LP's prog-blues opening diptych. "The combination, the way we did those two together, that was pretty clever," Betts says. "We always taped live. We would literally set the stuff up in the studio just like we were going to play (live), in a backline. That's the way we cut, from the first album right on through." (A notable exception: essential 1970 Allmans cut "Midnight Rider," for which tracks were stacked methodically, Betts says.)

The Allmans debut became a favorite of Mobile, Ala. band Wet Willie. "It really turned our heads around," recalls that group's frontman, Jimmy Hall. A friend of Wet Willie guitarist Rick Hirsch happened to work with Capricorn. This led to a summer 1970 audition for Walden and Fenter at a Macon warehouse, and Wet Willie became the second band signed to Capricorn. "It was a dream come true," Hall says. "Frank Fenter saw us as a Southern Rolling Stones." Whereas the Allmans featured guitars at the forefront, Wet Willie's sound was more soul, R&B and funk. Hall cites Redding, Pickett, Sam Cooke, James Brown and Sam & Dave as inspirations.

Wet Willie took up residence in a large Macon antebellum home at 1172 Georgia Ave. The house was only about five or 10 minutes from the Allmans' shared residence at 2321 Vineville Ave., the so-called Big House. "It was just a special time," Hall says, "because we were living there, writing songs in that house and having these big communal meals. It's a real bonding thing."

At Capricorn, that closeness extended from band to band. Hall recalls Allmans roadies helping load Wet Willie's gear and Betts offering advice on guitar amps. "It was a brotherhood and community," Halls says. While headlining a Spartanburg, S.C. club, Wet Willie's support act was local combo Marshall Tucker Band. Upon arriving back in Macon, Wet Willie gave Marshall Tucker's demo to Walden and Fenter and helped set up a show at Macon hotspot Grant's Lounge. Marshall Tucker signed with Capricorn, releasing now-classic songs like their heartbreak jam "Can't You See."

Meanwhile, Hall and Hirsch penned a Wet Willie tune called "Keep on Smilin'" boasting a reggae-ish riff and infectious, can-do lyrics. It became a Billboard Hot 100 top 10 smash. One early '70s night, Hall was summoned to Capricorn Studios to jam with English guitar hero Jeff Beck. Such began an ongoing bond; in recent years, Hall has been Beck's touring vocalist.

In the Allmans' lean, early Macon era, Betts recalls the band going to H&H Restaurant, where all six musicians would share two fried chicken dinners. When proprietor "Mama" Louise Hudson saw this, she brought out extra food to give the band. "That's what made being in Macon so dear to us," Betts says. "Stories like that."

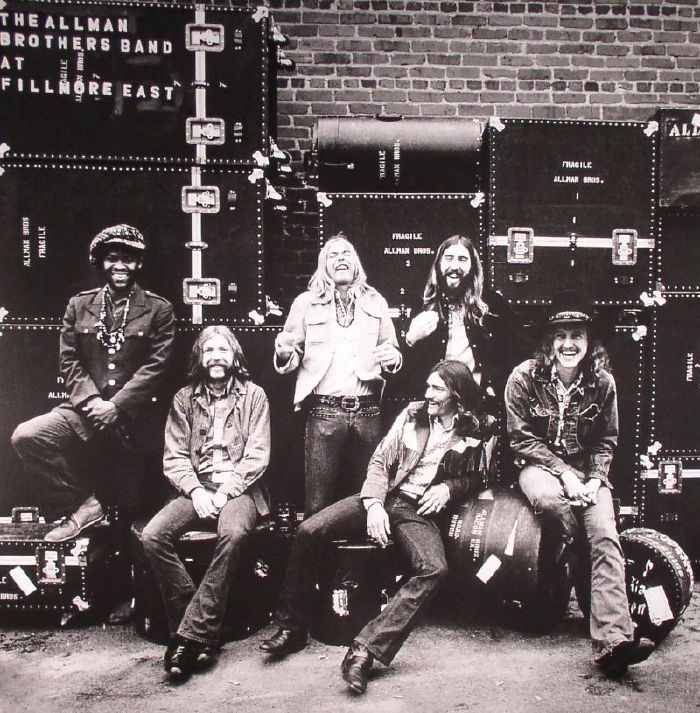

Unfortunately, tragedy struck the Allmans just as their star was finally rising after years of road work. In summer 1971 the band released At Fillmore East, an album capturing their spellbinding live show. (Alan Walden says the band's road manager had to panhandle to afford a toll bridge on the way to those New York concerts.) Just a few months later in Macon, Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident on Hillcrest Avenue.

"Duane was a real fireball. A straight shooter and real energetic guy and he really had a vision," Betts says. "He was a damn triple Scorpio. If you don't believe in the astrological signs and follow that stuff, that's a real strong, strong positive kind of sign. I loved Duane and got along great with him. I think about some of the conversations we had and they were like we were much older men. We were in our early twenties talking about things like being jealous onstage and what a horrible thing that is to a band. We talked about a lot of things like that. What breaks bands up. He was a hell of a guy."

Alan Walden says when Allman played slide guitar, "he didn't ask for your attention, he demanded it. He played on some of Eric Clapton's things … 'Layla' is really Duane Allman. And he was a great bandleader. Duane didn't take anything off anybody in the band."

At Fillmore East became Capricorn's first hit album. "That turned the whole situation from being a drain of funds to starting to make a few dollars," Walden says. "By the time that album really hit you're talking major dollars coming in." This continued with the group's third album, 1972's Eat a Peach, a mix of studio tracks recorded before and after Duane's death and At Fillmore East outtakes. Betts penned that LP's Les Paul-kissed love song, "Blue Sky," at the Big House. "I was sitting in the living room," he says. "It came kind of natural."

In 1973, the Allmans brought in 20-year-old keyboardist Chuck Leavell, who'd toured with Dr. John, to cut fourth album Brothers and Sisters at Capricorn Studios. "The recording studio right there in town, it was just so convenient and felt good to us," Betts says. The studio's key features included an API recording console, basement echo chamber and a nine-foot Steinway Model D grand piano purchased from Carnegie Hall. On the Steinway, Leavell played gorgeous melodies for "Jessica," an instrumental named for Betts' daughter and musically inspired by Romani-French guitarist Django Reinhardt.

Betts also had brought to those sessions a wistful road song with a chorus partially inspired by a ranch-hand friend. Betts had written "Ramblin' Man" at the Big House kitchen table, in the wee hours on acoustic guitar. It became the Allmans' lone Hot 100 top 10, peaking at No. 2. "Back then AM radio was top 40," Betts says. "We didn't like it when they played our stuff on AM, we thought that was corny stuff." Too bad -- the Allmans became superstars.

Eventually the group and Walden had a falling out over business matters. Still, Betts says, "There wouldn't be an Allman Brothers Band if it wasn't for him. He had a very good musical ear for real talent, what was good and what was just kind of OK, which makes a lot of difference. When you're trying to be in the record business, just OK isn't good enough." Leavell adds Phil Walden was "fearless" and "protective of artists he worked with." Alan Walden says Phil "loved the Allman Brothers and dedicated his life to them."

Betts calls Fenter, who died in 1983 from a heart attack, "one of my best friends" who advised him of music biz pitfalls. "He was a boxer earlier in his life and a very funny guy. Very worldly and intelligent."

Leavell has been The Stones' touring keyboardist since 1982. He's also worked with Clapton, George Harrison and David Gilmour. But pre-Allmans, when Leavell wasn't sure he'd have enough to eat that week, Fenter would happily give him a $200 check to get by. "He'd always try to help an artist in need," Leavell says. Leavell even met his eventual wife Rose Lane at Capricorn, where she was Fenter's assistant.

Capricorn is known for Southern rock. But it was more than that. The label's acts included soul singers Dobie Gray and Bonnie Bramlett; hard rockers Hydra and Captain Beyond; country-folkers Cowboy and Jonathan Edwards; trippy combo White Witch; fusion band Dixie Dregs; and blues-bop vocalists Elvin Bishop and Delbert McClinton.

Capricorn music later influenced rock bands like The Black Crowes, whose multi-platinum 1990 debut album Leavell played keys on. But Betts believes the label made a bigger impactelsewhere: "Country has been influenced immensely by Southern rock. Country radio stations wouldn't even play 'Ramblin' Man' when it first came out because the deejays said, and I quote, 'It's psychedelic.' [Laughs] That tells you where country music has been, and where it's come to these days."

After a decade or so run, Capricorn went under. Alan Walden says changing musical tastes, particularly the disco craze, contributed. "The biggest thing was my brother developed a heavy cocaine habit," Walden says. "And it just got out of hand, period. You're talking about a man who made $14 million one year and was filing for reorganization a year later. He was drinking heavy. He got all the way down to a one-bedroom apartment, just him and his dog."

But Phil Walden got sober. He began managing "Hey, Vern!" comedian Jim Varney, whose career took off. In the '90s, Capricorn rebooted, signing jam bands Widespread Panic and Col. Bruce Hampton. Sales wise, Capricorn 2.0 had better luck with alt-rock groups Cake and 311. They even released eventual country superstar Kenny Chesney's first album. "My brother was notorious for making comebacks," Alan says.

Alan Walden left Capricorn in the early '70s and managed Lynyrd Skynyrd. He says Capricorn passed on that "Freebird" band because Phil thought Skynyrd's Ronnie Van Zant "couldn't sing" and "was too cocky." Sibling rivalry, much? "Like many brothers," Alan says, "we had years we were close and years we weren't on the same page."

Before being diagnosed with cancer, Phil planned to get more involved in films. At the time, he and Alan were not on good terms. Phil was upset with a magazine interview Alan had done. But before Phil passed in 2006, Alan visited him in the hospital, told him he loved him, that Phil was "the genius of the family" and thanked him "for giving me a life." Despite his own management and publishing success, Alan, now 76, has lived in his older brother's shadow. "But these days," Alan says, in his elegant Georgia accent, "I'm glad I'm Phil Walden's brother."

Capricorn Studios fell into disrepair and there was talk of demolishing it. Alan Walden recalls tearing up as movers rolled the Steinway out of the studio. But in 2019 the facility is rising again as Mercer Music at Capricorn, thanks to Macon's Mercer University. The 20,000-square-foot multi-purpose facility will feature rehearsal spaces, a Capricorn museum and a refurbished studio.

"Some of the magic that was there is still going to be in that room," Leavell says. "There's no doubt about it."

Leavell will led a Dec. 3th Macon City Auditorium concert celebrating the studio's public re-opening, with Hall, Johanson, Cowboy guitarist Tommy Talton, bluesman Taj Mahal and Widespread Panic's John Bell performing, as well as newer artists like Marcus King, Brent Cobb and Betts' son Duane Betts.

Unfortunately, Gregg Allman wasn’t there. Southern rock's most famous star, Gregg died in 2017 from cancer complications. Betts was controversially ousted from the Allmans in 2000, but reconnected with Gregg before the end, calling every couple days to check in. The last time, Allman was so weak he could only listen and try to whisper back over the phone. Betts calls Allman, "One of the greatest blues singers this country has produced. He lived a long and full life … We have to find things like that to say, but it was sad."

After the Allmans splintered, Leavell formed fusion combo Sea Level, whose Capricorn releases include 1978's On the Edge. He cites Betts' country-tinged 1974 solo album, Highway Call, as an all-time favorite from the label, as well as Gregg's lush solo debut, Laid Back, the recording of which overlapped with Brothers and Sisters and featured Leavell's nimble piano.

If Gregg were around today, Leavell thinks "he would look back with a big smile and some degree of pride knowing we created music that stood the test of time. It's been 50 years, man. It's pretty nice to know that music is still being listened to, and I think it will in another 50."

Editor’s Note: Eat a Peach was a defining time of music for me personally. I loved every song on the album and actually bought it while working at my first music job at International Music Store. Amazing it has been 50 years! Sandy Graham