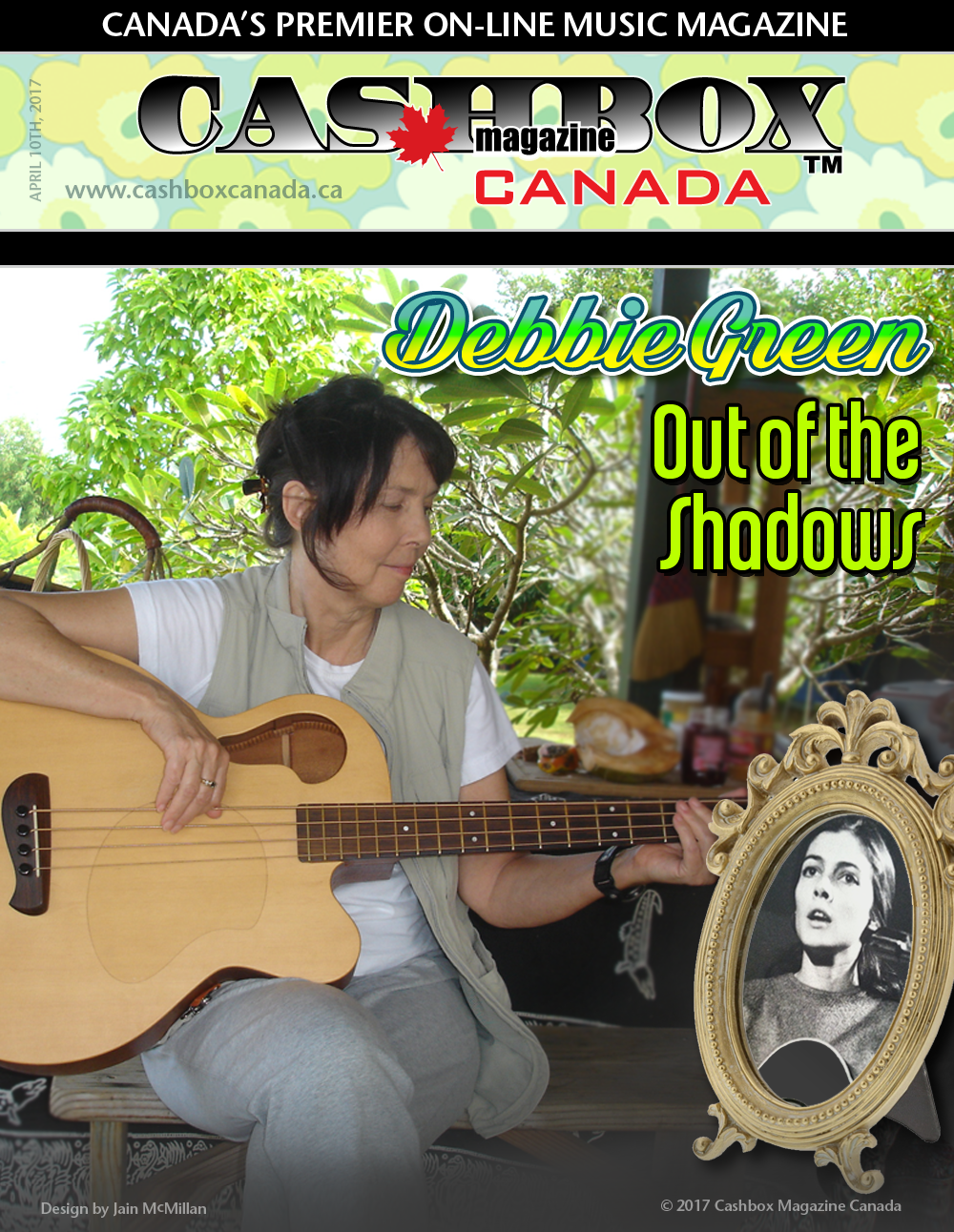

Debbie Green is not a household name but to the musical giants she influenced, taught and mentored she is a cornerstone to their careers and musical force to be revered and respected.

It’s best to go back to the beginning to get the full story on her influence on the folk music boom of the 50’s in America and beyond.

Deborah Green was born in New York City in 1940, her Dad was Vice President at Macy’s Department Store and her mother devoted a lot of her time and energy to charity work. Her life was middle class normal, growing next to a golf course on Staten Island. Her life changed when her parents split up when she was four years old.

She enrolled in The Putney School, a boarding school in Vermont. The school had a good music program and it was there that Debby showed her interest in music.

On a horse-back riding/camping trip, a fellow student took out a guitar while sitting around a campfire. “One of my brothers had taught me some chords on his ukulele so I just added the other two strings. I was hooked. I spent summers going into the Village to the 8th Street record store and buying everything in the folk bin. Odetta, the Clancy Brothers, Ewan McColland, Peggy Seeger, The Weavers and Harry Belafonte. It was the late 50s so the bin wasn’t that big at the time.” She would sit and watch closely the fingerpicking styles of the likes of Dave Von Ronk, up close and personal, memorizing their patterns. “I sat on the floor at house concerts in the front row watching his fingers.” A trip to the city would take her about an hour and half by ferry from Staten Island to New York City and then on a subway to The Village. On the long trips home she would replay the syncopation patterns she had just heard and seen. It was quickly becoming her passion.

Later Debbie enrolled in Boston University Theater School. “Freshman orientation was mandatory. They piled a thousand very noisy kids in busses out to some huge gymnasium. I was sitting on the floor with my friend Margie from Putney. We were talking about life, deep stuff, trying to tune out all the bedlam. Someone handed us some beanies then later came and told us we had to wear them. Thank you but no, not our style. We were told that each time we were caught not wearing our beanies we would be fined 25 cents. This was in effect until the college won their first football game. Horrified, we looked around and out of a thousand kids there was a couple also sitting on the floor in the corner, also protesting the beanie tyranny.” That couple was an eighteen year old Joan Baez and her friend Doug. The four anti-beanie revolutionaries walked out of the orientation and jumped into a car that had a guitar resting in the back seat. Debbie picked up the guitar and started playing. At that time, Joan knew two songs (Dona Dona and La Bamba) but was interested in learning more. Joan studied carefully as Debbie taught her the chords and arrangements to her entire repertoire of songs, which Joan then recorded and released as her first two albums. Joan, being a “master of mimicry” had all Debbie’s body language impact of these sorrowful love ballads down pat so that whenever Debbie sang her own material, she became a Baez imitator. Debbie moved on to more rhythmic American folk songs finger picking style. She had been instrumental in starting the folk revival, being one of the first performers at the now famous birthplace of the movement, the Club 47 Mount Auburn, off Harvard square in Cambridge. It was time to move on and in 1960 she moved to Berkeley, California. “Berkeley was great but there was one thing missing. It didn’t have a Club 47 Mount Auburn.” So to fill that void Debbie and some friends opened The Cabale, later known as the Club 47 West. The booming folk revival now had a west coast venue.

“People who played the Ashgrove in L.A. would come up to The Cabale, people like Hopkins, Tom Paxton, Lenny Bruce. And the Cambridge crowd, Jim Kweskin, Spider John Keorner and others. Jesse Fuller of San Francisco Bay Blues fame and local artists, Janice Joplin, Country Joe before the Fish and John Fahey. Big Mama Thorton and the newly re-discovered Bukka White, the legendary blues artist of ‘Parchment Farm’ fame.”

And it was a place for Debbie to play as well. But she was starting to battle persistent pulmonary problems due to “some serious childhood asthma.” And so she had to put the solo singing career on hold.

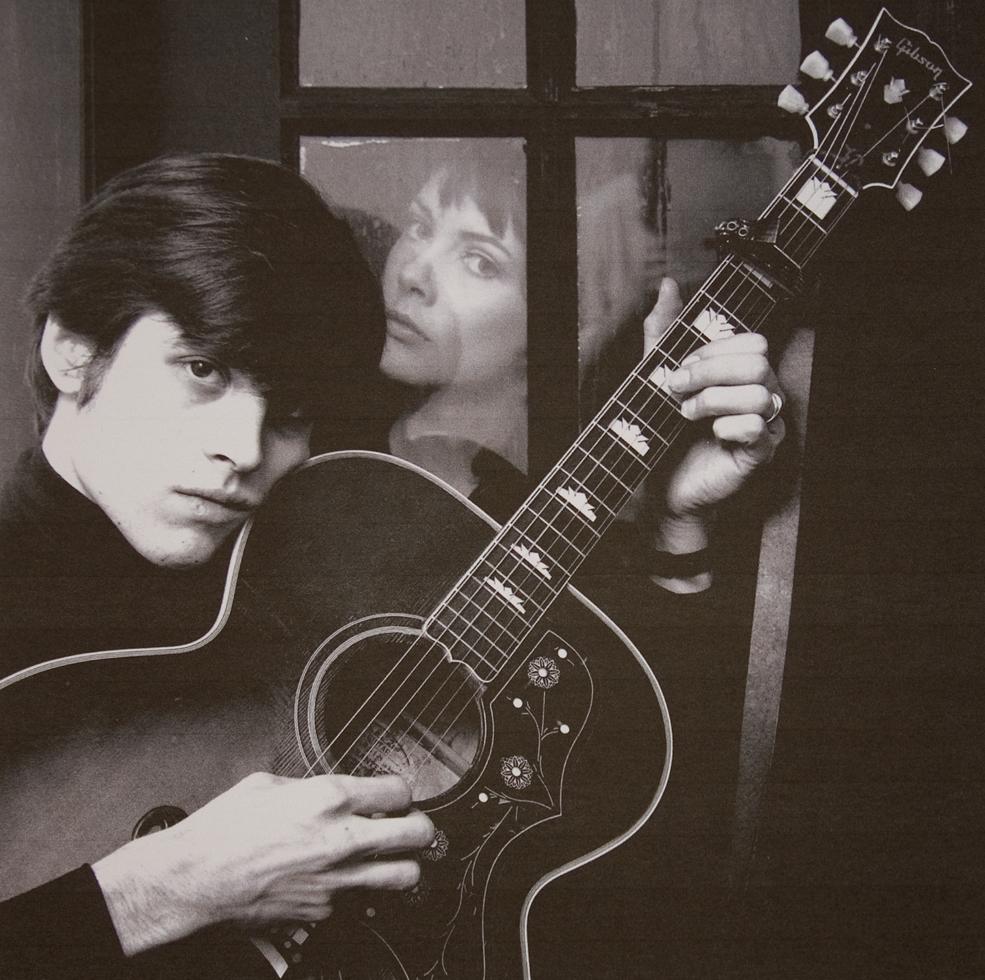

It was at Berkley she met her future husband, singer/songwriter Eric Andersen, who later became a voice of protest in the Greenwich Village along with Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, and Tom Paxton.Eric had this to say, “Debbie Green is a beautiful fantastic musician who was a friend to Pete Seeger, an early Club 47 performer, taught Joan Baez her first albums of songs at Boston University and performed on many of my shows and albums, playing guitar and piano and singing harmonies. From the Vanguard albums to Blue River and beyond. Debbie taught me and Eric Clapton finger-picking in the sixties. She also played bass with many artists. We have a beautiful daughter, Sari who is also a singer/songwriter so I guess it’s in the blood.”

Norbert Putman,famed producer, (which included Eric Andersen’s “Blue River”) bass player and most recently the author of a book of his memoirs title “ Music Lessons Volume 1” had this to say about Debbie, ”Debbie Green is one the most talented women I have ever met and her contribution to “Blue River “was huge. “

During the rest of the 60’s, Debbie toured and recorded with Eric Andersen, and was an important element inthe recording of Eric’s hit albums ‘Today is the Highway,’ ‘Bout Changes ‘n’ Things,’ and ‘Blue River’. She was also intimately involved in the production of ‘Stages–The Lost Album,’ which was intended to be the follow-up to Eric’s very successful ‘Blue River’. Somehow, forty boxes of master tapes were lost in the vaults of Columbia Records for twenty years, before being found and finally released to some acclaim in 1990.

In 1965, Debbie and Eric moved to a loft on Spring Street in New York. The area later became known as SoHo, but at the time those lofts were filled with rag bails and odd little factories. It was ‘Little Italy’ - Mafioso territory. She had been playing backing guitar on Eric’s shows. Her musical talent continued to shine when she added piano to her list of instruments. “Paul Harris was playing piano with Eric but he had to drop out. We had a gig in two weeks and I told Eric I thought I could do it. So I practiced all those keys. I didn’t get the ragtime down but was able to play the gig.” Arty Traum said that Dylan once described Debbie as “a great piano player” after he heard her play with Eric Andersen at the Cafe a Gogoin Greenwich Village on Bleeker Street in 1966. She later toured with the Happy and Artie Traum band, playing piano. New York in the 60’s was a vibrant place to be. Touring the country and recording sessions in New York and Nashville made a very full life. It brought Debbie into contact with the musical elite of the US and England, as well as the civil rights movement in America.

In 1966, Jack Newfield, a writer from Village Voice, invited Eric and Debbie to be part of the drive to allow black people to vote. Newfield had been contacted by someone in Mississippi to come down and help, so the three flew into Atlanta and drove down to Liberty, Mississippi - right at the time when Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner had been murdered by the KKK. “It was a long highway, pitch dark and we were terrified. There was a civil rights worker who had a crush on Eric who really didn’t want me around. She said Eric could stay, but I would have to go to another house over the Alabama border. Well, we decided if were going to die, we were going to go together, so we refused.”

The New York years also introduced Debbie to the musical elite of the US and England. “Eric’s Andersen publicist got him a spread in the first issue of US Magazine. The story line was supposed to show us going to vintage clothing stores and then to the tailor to get fitted and coming out with very trendy duds. The London scene was really into clothes at the time. I think it was 1968. But really all we ever wore were jeans and t shirts. ”Eric Clapton was in that same issue of “US”, and had been convinced by the magazine article that Eric and Debbie were trend setters in fashion. “He was a little puzzled by our lack of interest in our attire.” Always the teacher, Debbie gave Clapton her finger-picking course. “He was already famous with Cream but had not played finger style.”One late night, stumbling home from the village, we brought Clapton and Jimi Hendrix with us, figuring they should know each other. Jimmy had a lot of acid with him and we all took some. We had this upright piano which had been painted canary yellow and I was playing through a keyboard engulfed in flames, very distracting. I kept thinking that I should be listening to Clapton and Hendrix, who were both wailing electric guitars behind me,vaguely aware that this was probably a historic moment and I should try to listen and remember. I do remember a wall of sound but no individual notes.That went on till well past dawn, par for the course back then.”

The Village was such an exciting place in those days. All the working musicians who were not on tour would finish the evening at the Bitter End,sitting at tables, sawdust on the floor. Fame was bursting out all over. You could drop in The Café Au Go Go at any time and find the Mamas and Papas rehearsing, Hendrix doing his first show downtown. James Taylor, Frank Zappa at The Village Vanguard and Buffy Saint Marie.

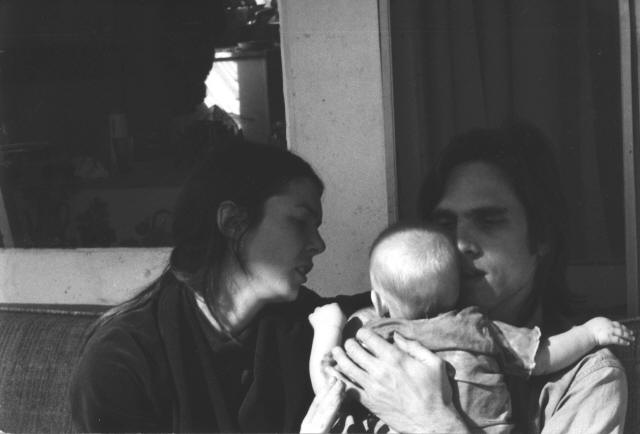

In 1970 Eric and Debbie moved to California and had a daughter, Sari. She went along with them to gigs, and recording studios in Nashville. When Sari was one, they bought a house in Mill Valley in Marin County. But now Debbie had to focus on a child and be an adult, and that changed the rhythm of the marriage. She moved back east with Sari to Woodstock for a few years, and did some short tours playing piano with Happy and Artie Traum.Sari, who lives in Hawaii says, “ Mom basically gave up her career to raise me.” Ironically Sari di the same thing for her children but is now working on a new project.

In 1972 Debbie took up the electric bass. She describes walking up a driveway in Woodstock to Harvey Brooks’ house. “Someone was playing bass and I just heard how powerful that instrument was rhythmically. I started listening to the perfect pocket where each note was placed. Then I realized he was only playing one note, the same note through the whole jam. It turned out to be Ben Keith the steel player, not Harvey, playing the bass. At that moment I knew the power of that instrument, and that I had to get one.”

Soon after that the bass became her instrument and she went on the road with Hoyt Axton one summer with the tour ending up at the Willie Nelson Picnic. She also played with Mimi Farina around the country, and with local bands out of San Francisco. She toured Northern California playing behind Tim Hardin. “Tim didn’t want to rehearse. He would just start making up words, bits and pieces, and I had to make it into a song right there on the spot. That’s the way all the gigs went. So I got good at thinking up a pattern right there on the stage as the set progressed. Trouble was I’d have to remember the pattern and repeat it until the song was over.”

In 1974, after dinner in the village with Eric Kaz, “We were walking east on Bleeker Street. Not a soul in sight, a big wind picking up street debris, papers swirling in the air like ghosts of the Village in the 60’s. It was sad, all that life gone. We were walking past the Bitter End and suddenly the big metal stage door burst open and Bobby Neuwirth popped out and ushered us right up onto the stage.”

“He introduced us as the greatest harmony singer that ever lived and Eric Kaz the famous songwriter. Kaz was playing the piano at the back of the stage and singing one of his new songs that I had never heard. Hard to sing backup harmony when you don’t know what chords are coming. I was on mic at the front of the stage, spotlight blasting so you could only feel the audience there behind the blackness. To cover not knowing the song I would move my lips and pretend the mic was intermittently on the blink. But the odd thing was there was this electricity in the air. A vibrating nervous energy! I’m looking out on a black house and after a few minutes I realized that Dylan must be out there. It was always like that when Dylan was around. You could feel the vibe before you knew he was there. It turned out to be a show that Neuwirth was putting on for Dylan so he could hear a bunch of people - like an audition - for the Rolling Thunder Review that they were putting together.” The ghosts of the village were very much alive inside that room.

When Debby got back to the Mill Valley house that summer, she got a letter from Dylan inviting her to sing on the record they were making to take on the Rolling Thunder Review. But it was too late. “I couldn’t have gone on tour for that long anyway. Sari was in school and I was a mom.”

In the late 80’s when the home studio started to become affordable, Debbie became interested in recording again. She always heard musical hooks andmelody lines, and wanted to get them down. Her love of singing harmonywas based upon those moving composition lines.

So she began to build a recording studio - just as the midi and digital recording revolution took off. George Madaraz, her long time co-conspirator,came to assist her with her computer needs, and has refused to leave eversince. They currently operate a ProTools studio in Mar Vista, CA called George Green Studios.“I was just testing the studio to see what I could do. I decided to do one of my favorite Eric Andersen songs, Listen to the Rain.” Debbie laid down the guitar with her famous Gibson J-200, then the bass and percussion. She played all the instruments on the track, adding a lone midi mercado violin for a counterpoint hook. That was the first time she realized she really could do a whole track on her own. She got her daughter Sari to sing the lead and they finished up together doing the backup vocals. That was Sari’s first recording.

Debbie has recorded, mixed and released a number of albums from George Green, including an amazing collection of original songs by long-time friend Bruce Langhorne named ‘Tambourine Man.’ “Bruce played with everyone in the sixties. He played guitar on some Dylan classics and was the subject for the song Tambourine Man. Later he spent a decade doing film scores. We both had studios, and Bruce was doing some really innovative stuff. He asked me to produce him. That is one of my favorite projects of all time.”

Debbie is currently finishing up the final touches on a record she has co-produced, played on and sang harmonies with her daughter called 'Sari The LA Sessions'. "The advances in technology have made it possible to even do realistic drums, not the midi programmed drums that sound so artificial, but real drummers playing a groove. You keep the groove but just change the hits around to fit the syncopation of the song that you're adding them to.".

But her most exciting discovery was being able to compose orchestral lines to a song. " My first real string arrangement was for Sari's song 'Say It Again.' I used a lot of strings on this album. If I had another life to lead that's all I'd be doing is composing.It's because of Sari's songs that i got do it." She wistfully remarked " It took me a long time to get there."

The link to the You Caring page is:

https:

We hope this story will bring to light a great talent who has lived in the shadows and is now in need of the bright light of our help and compassion.